Welcome to my Time Machine on Substack.

In addition to my regular columns for the Free Press and journalism elsewhere, I intend to publish here all the writing and talking I do that belongs under the heading of applied history.

Applied history is a term I first began to use nearly ten years ago to distinguish my work from a great deal of what passes for history nowadays. I do not claim to have originated it. The first use of “applied history” of which I am aware was as the title of an obscure Iowa journal in 1912. And I have been only one of several scholars—including Graham Allison at Harvard and the founders of the new Journal of Applied History—who have sought to promote the idea more recently.

Put simply, the point of applied history is to illuminate contemporary problems with past experience derived from serious study. But the fun of applied history is quite simply time travel itself.

When I was a boy, there was only one superhero I revered, and that was Doctor Who, the Time Lord. The heroes of the American Marvel comics were creatures of implausible muscularity in gawdy body stockings. But the Doctor used only his powerful brain (and his sonic screwdriver) to overcome his adversaries. Endearingly, he also dressed like a rather eccentric Oxford don. More importantly, thanks to the Tardis—a marvelous spaceship disguised to look like one of the old police telephone boxes that used to exist in England—Doctor Who had the power to travel through time as well as space. This superpower always fascinated me in a way that the abilities to make giant spiderwebs or morph into an enraged green giant did not. I now realize this early fascination with time travel was one of the reasons I became an historian. For the only way to travel backwards through time—and, I would say, also forwards—is to immerse oneself in the study of the past. (A Ukrainian friend likes to say that one achieves a similar result by drinking wine—the older the vintage, the further back one goes. The two methods are compatible.)

“If Time is really only a fourth dimension of Space,” asks the Medical Man, one of the unnamed professionals at the start of H.G. Wells’s great novel The Time Machine, “why is it, and why has it always been, regarded as something different?” The Medical Man hypothesizes that it is because “you cannot move at all in Time, you cannot get away from the present moment.”

“My dear sir,” [replies the Time Traveler, in whose home they are meeting] “that is just where you are wrong. That is just where the whole world has gone wrong. We are always getting away from the present moment. Our mental existences, which are immaterial and have no dimensions, are passing along the Time-Dimension with a uniform velocity from the cradle to the grave. Just as we should travel down if we began our existence fifty miles above the earth’s surface.”

“But the great difficulty is this,” interrupted the Psychologist. “You can move about in all directions of Space, but you cannot move about in Time.”

“But you are wrong to say that we cannot move about in Time. For instance, if I am recalling an incident very vividly I go back to the instant of its occurrence: I become absent-minded, as you say. I jump back for a moment. Of course we have no means of staying back for any length of Time, any more than a savage or an animal has of staying six feet above the ground. But a civilised man is better off than the savage in this respect. He can go up against gravitation in a balloon, and why should he not hope that ultimately he may be able to stop or accelerate his drift along the Time-Dimension, or even turn about and travel the other way?”

The Time Traveler then reveals a model of his machine. “Now I want you clearly to understand,” he says, “that this lever, being pressed over, sends the machine gliding into the future, and this other reverses the motion. This saddle represents the seat of a time traveler. Presently I am going to press the lever, and off the machine will go. It will vanish, pass into future Time, and disappear.” Later he shows his friends the almost-complete time machine itself. “Upon that machine,” he tells them, “I intend to explore time. Is that plain? I was never more serious in my life.”

Well, I was never more serious in my life. For I have come to realize that our species is rapidly losing the ability to engage in the form of time travel we call the study of history. Surveys on both sides of the Atlantic (see here and here) reveal a dismaying ignorance of history, especially amongst young people. Worse, charlatans seem able to command immense audiences by spouting torrents of lies about the past, the most egregiously mendacious example this year being the conversation between Tucker Carlson and a huckster named Daryl Cooper. A proliferation of podcasts in which people chatter about history testifies to the public’s sincere interest in the subject. But the unreliability of such products can scarcely be overstated. Most podcasts have all the rigor of pub banter.

Meanwhile, in schools and universities, the teaching of history has become woefully distorted by the ideological preoccupation of the contemporary “progressive” left with the politics of racial and sexual identity. In The History Boys, the playwright Alan Bennett posed a “trilemma”: Should history be taught as a mode of contrarian argumentation, a communion with past Truth and Beauty, or just “one fucking thing after another”? He was evidently unaware that today’s high-school seniors are offered none of the above. (If they are lucky, they may get one thing fucking another—for what else is the history of sexuality?) And most history courses offered in the history departments of major universities are now so unappealing that only a dwindling number of students choose to major in history. As might be expected, the demand for history professors has also slumped.

The net result is that both the elites and the public, in the English-speaking world and beyond, are increasingly remote from historical understanding. This does not equip either group to arrive at sensible decisions about the problems they confront. For without the application of history, decision-making on any issue is akin to a game of darts played in a darkened room. Nor does it equip people to contradict the fallacious but apparently historical arguments of the sort that the Russian president is fond of publishing, notably on the legitimacy of an independent Ukrainian state.

An eminent economist once confessed to me that, when he had been an undergraduate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his mother had implored him to take at least one history course. The prodigiously intelligent youth had replied that he was more interested in the future than in the past. It is a preference he later learned to be illusory. There is in fact no such thing as the future, singular; only futures, plural. There are multiple interpretations of history, to be sure, none definitive—but there is only one past. And although the past is over, for two reasons it is indispensable to our understanding of what we experience today and what lies ahead of us tomorrow and thereafter.

First, the current world population makes up approximately 7 percent of all the human beings who have ever lived. The dead outnumber the living, in other words, fourteen to one, and we ignore the accumulated experience of such a huge majority of mankind at our peril. Second, the past is really our only reliable source of knowledge about the fleeting present and to the multiple futures that lie before us, only one of which will actually happen. History is not just how we study the past; it is how we study time itself. And any theory in the realm of economic or political science must at some point submit itself to data, which are almost always a species of historical record.

Of course, my discipline has limitations. We historians are not scientists. Unlike Isaac Asimov’s “psychohistorian” Hari Seldon in Foundation (1942), we cannot (and should not try to) establish universal laws of social or political “physics” with predictive powers. Why? Because there is no possibility of repeating the single, multi-millennium experiment that constitutes the past. The sample size of human history is one. Moreover, the “particles” in this one vast experiment have consciousness, which is skewed by all kinds of cognitive biases. This means that their behavior is even harder to predict than if they were insensate, mindless, gyrating particles. Among the many quirks of the human condition is that people have evolved to learn almost instinctively from their own past experience. So their behavior is adaptive; it changes over time. We do not wander randomly but walk in paths, and what we have encountered behind us determines the direction we choose when the paths fork—as they constantly do.

Henry Kissinger (the second volume of whose biography I am writing) put it well in 1957. “History teaches by analogy, not identity,” he wrote. “No significant conclusions are possible in the study of foreign affairs … without an awareness of the historical context [because] history is the memory of states.”

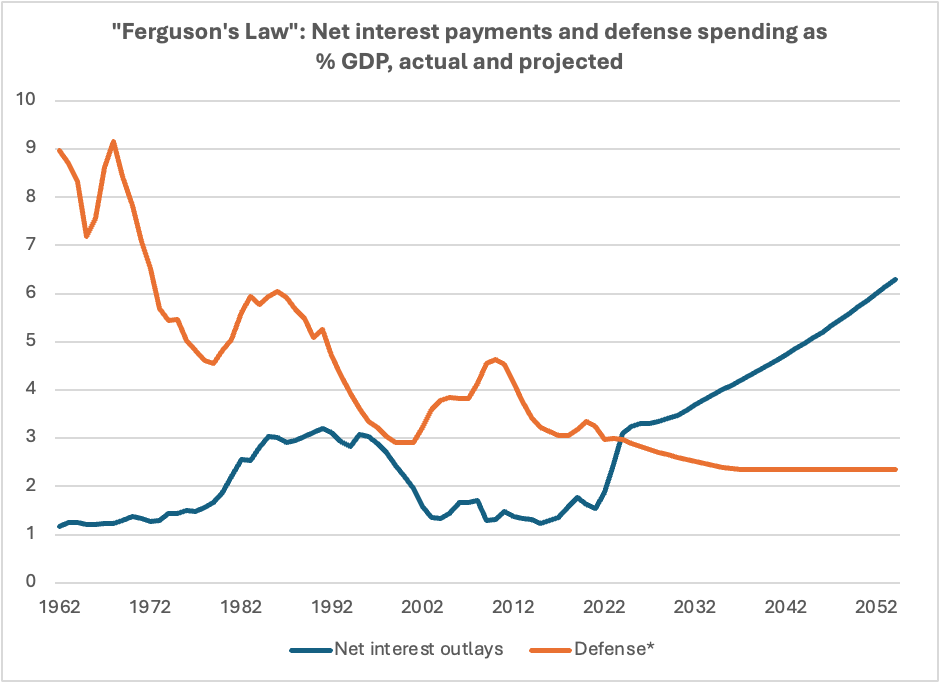

So what can historians do? First, by mimicking social scientists and relying on quantitative data, historians can devise “covering laws,” in Carl Hempel’s sense of general statements about the past that appear to cover most cases. For instance, I have suggested that when a great power spends more on debt service than on defense, it will not be great for much longer, a proposition that appears to be true of the Habsburg Spain, the Dutch Republic, Bourbon France, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire. (I have half-seriously called this Ferguson’s Law.) It should therefore be a cause for concern that the United States today, for the first time, spends more on interest payments on the federal debt than on national security.

Alternatively—though the two approaches are not mutually exclusive—the historian can commune with the dead by imaginatively reconstructing their experiences in the way described by the great Oxford philosopher R. G. Collingwood in his 1939 Autobiography. (What follows will be familiar to any who has read the introduction of my book Civilization. I make no apology for repeating it, as it is fundamental to my philosophy of history.)

Collingwood’s ambition, forged in the disillusionment with natural science and psychology that followed the carnage of World War I, was to take history into the modern age, leaving behind what he dismissed as “scissors-and-paste history,” in which writers “only repeat, with different arrangements and different styles of decoration, what others [have] said before them.” His thought process is worth reconstructing:

a) “The past which an historian studies is not a dead past, but a past which in some sense is still living in the present” in the form of traces (documents and artefacts) that have survived.

b) “All history is the history of thought,” in the sense that a piece of historical evidence is meaningless if its intended purpose cannot be inferred.

c) That process of inference requires an imaginative leap through time: “Historical knowledge is the re-enactment in the historian’s mind of the thought whose history he is studying.”

d) But the real meaning of history comes from the juxtaposition of past and present: “Historical knowledge is the re-enactment of a past thought incapsulated in a context of present thoughts which, by contradicting it, confine it to a plane different from theirs.”

e) The historian thus “may very well be related to the non-historian as the trained woodsman is to the ignorant traveler. ‘Nothing here but trees and grass,’ thinks the traveler, and marches on. ‘Look,’ says the woodsman, ‘there is a tiger in that grass.’” In other words, Collingwood argues, history offers something “altogether different from [scientific] rules, namely insight.”

f) The true function of historical insight is “to inform [people] about the present, in so far as the past, its ostensible subject matter, [is] incapsulated in the present and [constitutes] a part of it not at once obvious to the untrained eye.”

g) As for our choice of subject matter for historical investigation, Collingwood makes it clear that there is nothing wrong with what his Cambridge contemporary Herbert Butterfield condemned as “present-mindedness”: “True historical problems arise out of practical problems. We study history in order to see more clearly into the situation in which we are called upon to act. Hence the plane on which, ultimately, all problems arise is the plane of ‘real’ life: that to which they are referred for their solution is history.”

These two modes of historical inquiry allow us to turn the surviving relics of the past into history, a body of knowledge and interpretation that retrospectively orders and illuminates the human predicament. Any serious predictive statement about the possible futures we may experience is based, implicitly or explicitly, on one or both of these historical procedures. If not, then it belongs in the same category as the horoscope in this morning’s newspaper.

In my Time Machine, then, we shall go in search of the tigers in the grass. Most of what I post here, aside from columns written for The Free Press, will be free to subscribers. However, as Samuel Johnson famously told James Boswell, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” I shall therefore quite deliberately make some (especially interesting) material accessible only to paying subscribers. They will also be given preferential access to video and audio content.

The spirit of this enterprise is encapsulated by a painting by Titian, his Allegory of Prudence, which he completed at some point between 1550 and 1565.

Look closely and you can see that there in an inscription. It reads:

EX PRÆTE/RITO // PRÆSENS PRVDEN/TER AGIT // NI FVTVRA / ACTIONĒ DE/TVRPET

This translates as: “Learning from Yesterday, Today acts prudently lest by his action he spoil Tomorrow.”

A reproduction of the Allegory of Prudence hung in the original offices of Greenmantle in Harvard Square between 2011 and 2016. It was there that I first started to practice applied history, as I and my first employees sought to use our historical knowledge to illuminate the questions then perplexing investors and asset managers. Though Greenmantle’s research remains exclusively available to our clients, I nevertheless think a time has arrived when it is right to share at least some aspects of our methodology with a wider audience.

Financial markets are themselves a kind of time machine. Stock and bond markets exists so that informed traders can collectively estimate the net present value of the future earnings of a company’s stock, or the probability that a corporation or government may continue punctually and fully to pay the interest and principal due on its bonds in a currency not debased by inflation. A futures market allows participants to speculate on the future prices of commodities and securities. Unlike most historians, I have spent part of my career interpreting financial data as a source of evidence about contemporaries’ expectations of the future. And I have spent another part of my career seeking to anticipate these markets’ movements on the basis of historical insight.

The great lesson we learn from such work is that a very substantial proportion of future events lie in the domain of uncertainty. One simply cannot predict them, or even attach meaningful probabilities to them, on the basis of any reliable regularities, much less grand cycles of history.

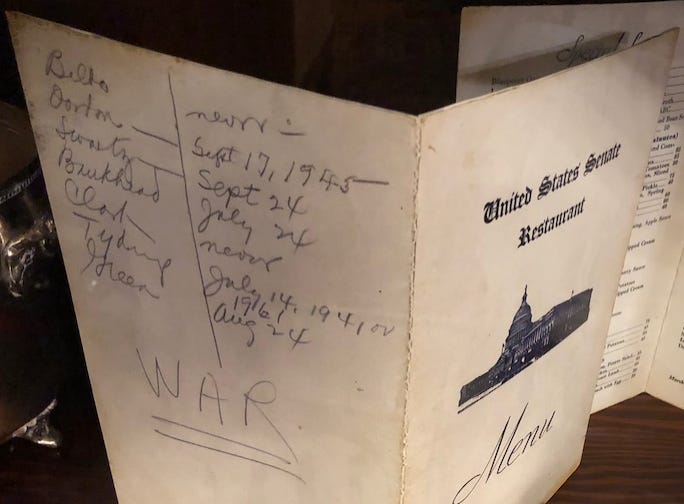

Let me illustrate the point with a striking American example. On March 24, 1941, seven members of the U.S. Senate had lunch in the restaurant where members of the American upper house still take their meals today. On the menu was mackerel, meat balls with spaghetti, and a “cold shore platter.” The conversation turned to the war that had been raging in Europe for a year and a half. The senators discussed when the United States would enter the war and recorded their predictions on the back of the menu. These ranged from “never” to “1961.” One thought “September 17, 1945.” However, four of the seven thought American involvement would occur within four, five or six months. It was of course eight months later, on December 7, 1941, that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Not one of these legislators—who, unlike their constituents, were privy to relatively high-quality intelligence about the war—got the date of U.S. entry into World War II right.

As Hugh Trevor-Roper wisely observed:

At any given moment in history there are real alternatives, and to dismiss them as unreal because they were not realized … is to take the reality out of the situation. How can we ‘explain what happened and why’ if we only look at what happened and never consider the alternatives, the total pattern of forces whose pressure created the event? ...

History is not merely what happened: it is what happened in the context of what might have happened. …

It is only if we place ourselves before the alternatives of the past, as of the present, only if we live for a moment, as the men of the time lived, in its still fluid context and among its still unresolved problems, if we see those problems coming upon us, as well as look back on them after they have gone away, that we can draw useful lessons from history.

One of the most important lessons of applied history is that the historical process is too complex to model, much less to prophesy, and that one must be prepared to be wrong sometimes. If one is wrong half the time, of course, one risks being replaced by the tossing of a coin. Over the years, however, I have been increasingly impressed by the performance of Greenmantle research, the predictive statements of which tend to be right roughly two thirds of the time—and more often than that on the epochal events of our time. In January 2020, for example, we rightly warned that the biggest pandemic since the 1918-19 Spanish Influenza was unfolding. In February 2021 we foresaw the inflationary consequences of fiscal and monetary policy mistakes. In December 2021 we correctly predicted the Russian invasion of Ukraine three months later. And regularly in the months before October 7 last year we warned of an attack on Israel.

In a future post on Time Machine, I will provide a review of applied history as practiced by Greenmantle over the past 13 years, to illustrate how exactly we go about spotting the tigers in the grass. It is a valuable skill.

This is excellent. Very much looking forward to learning from your and the Greenmantle team's insights.

The measure of a great piece is the prompt it gives to new thoughts, possibly tangential to the actual topic discussed. In this case, the mention of financial markets as predictors (poor) brings to mind the role of financial market volatility as predictor (better). In this way, information science emulates the history you describe - a rise in volatility indicates a decline in information entropy in the system and a collapse in the number of possible future pathways. At least, that's my contention.